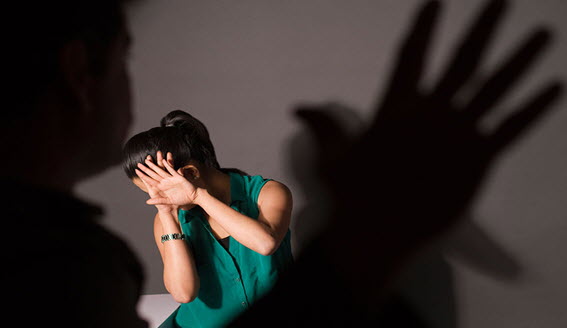

The recent murder of Noor Muqqadam at the Capital demonstrates once again the persistence of the South Asian experience of domestic violence.

The very familiarity of the middle-class, suburban setting for the extreme violence of this killing has provoked a conversation about a pattern of trusted personalities control and victimization that frequently acts as a pathway to murder.

Violence against women is one of the modern world’s most intractable problems. It is an expression of women’s inequality. In the Clarke case, it demonstrates their continuing vulnerability in spite of the otherwise general decline in interpersonal violence.

In a widely recognized trend in modernizing societies, homicide declined not just steadily but often swiftly. But this decline in violence is not shared equally. The Eastern empires that witnessed remarkable declines in violence in their home countries in the nineteenth century inflicted excessive violence on the people they colonized. And even within those societies showing a decline of violence, the benefits were more likely to be felt by men than by women.

Our research suggests that long-term homicide trends in Asian communities replicate this pattern. In the early to mid-nineteenth century, homicide rates in the Asian colonies were much higher than they were a century later.

Men are still killed in greater numbers than women by the late twentieth century, but the decline in risk of homicide was invariably far greater for men than women. So great was the change that by the inter-war years the rate of homicides per 100,000 women was greater in some years than that for men. The reasons for these changes – especially men’s declining risk – are inevitably complex. But for women, a disturbing reality continued.

Not only did their risk of homicidal death remain constant – they were always much more likely to be killed by an intimate partner than were men.

The reality of this picture has long been disguised by our preferred response to violence – through law and policing, and a focus on offenders. Official statistics on murder rarely counted the age and gender of those killed or their racial background. The reality of domestic murder, and the risk of being killed by a family member, was hidden away in official ‘cause of death’ statistics.

In mortality data, a murder is a rare event, its incidence drowned out by the volume of other causes, natural and otherwise. But the emergence in recent decades of a focus on the victims of violence has enabled us to understand anew the scale of a problem first recognized in the nineteenth century – the perils of the domestic environment for women and children.

FINAL THOUGHTS

We need to find ways to ensure that women’s equality means just that in a place where it continues to be most threatened, the home and the family

Let Us know thoughts!

Your email address & phone will no be published. Required fields are marked*